For the fans who packed Centre Court and Henman Hill on Friday afternoon at the All-England Club, the wrong Andy won the second gentlemen’s singles semifinal at the 2009 Wimbledon Championships. Even then, however, the eyes of a commonwealth had to appreciate the power of the moment Andy Roddick created on the world’s most famous tennis court.

For the fans who packed Centre Court and Henman Hill on Friday afternoon at the All-England Club, the wrong Andy won the second gentlemen’s singles semifinal at the 2009 Wimbledon Championships. Even then, however, the eyes of a commonwealth had to appreciate the power of the moment Andy Roddick created on the world’s most famous tennis court.

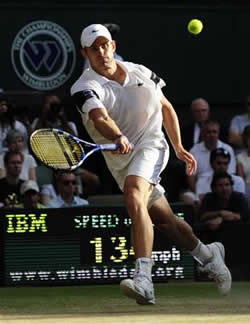

Playing nothing less than the best tennis match of a career rich in prize money but poor in terms of Grand Slam championships, the sixth-seeded Roddick came through in the clutch to oust third-seeded favorite Andy Murray in four riveting sets. The 6-4, 4-6, 7-6 (7), 7-6 (5) win catapults Roddick into Sunday’s final against second-seeded Roger Federer, while ending Murray’s bid to become the first British male to reach a Wimbledon final since Bunny Austin turned the trick in 1938.

Just how sweet is this breakthrough for Roddick? Words frankly can’t do justice to the magnitude of the American’s achievement, built on the back of ice-veins composure under pressure.

The most immediately satisfying aspect of this match for Roddick is that his tennis rose to sublime heights precisely when the former world No. 1 needed his best brand of ball. At love-40 in the first game of the third set, Roddick was about to cede scoreboard leverage and real-world momentum to Murray, who stormed back to win set two after dropping the opening stanza. However, the American-perhaps channeling Pete Sampras (whose record for slam singles titles is shared by Federer, and could be fully eclipsed on Sunday unless Roddick says otherwise)-climbed out of that ditch with uncommon resolve.

Sampras won seven Wimbledons by making the occasional well-timed escape from a love-40 hole in a late-tournament match. Today, Roddick turned that trick by hitting a tremendous backhand stab volley at 30-40 to level to deuce, and then smacking big serves to prevent Murray from working his way into rallies. Roddick would break Murray in the fourth game of the third set and eventually establish a 5-2 lead with rare touch and precision at net (the American won 48 points at net, converting a healthy 64 percent of all forays to the twine), but when serving for the set at 5-3, a loose and distracted game, combined with an inspired backhand passing shot from the Scotsman at love-30, enabled Murray to stay alive and eventually force a massive tiebreak.

No worries for Roddick-despite blowing a big lead, the sixth seed would rally, and again, his net play showed the way forward.

After Murray hit his third ace in as many service points to grab a set point in the breaker at 6-5, Roddick-on his own serve-saved his hide by executing a forehand drop volley that barely eluded Murray’s reach. After the two players traded service points for 7-all, a penetrating Roddick return of a Murray first serve drew an error from the third seed, and at 8-7, Roddick-armed with the mini-break-was able to serve for the set. The sixth seed didn’t waste his big chance-he used his serve to gain a territorial advantage on the point, which ended when a smart backhand approach forced Murray to attempt a high-risk forehand pass well behind the baseline. The Scotsman couldn’t find the range, and Roddick forged a two-sets-to-one lead. Steel nerves under fire had shepherded the 26-year-old through one towering trial.

In the fourth set, Roddick would call upon that resourcefulness once more, as another set careened toward the clamorous conclusion known as a tiebreak.

Locked yet again in an equally-weighted war (Roddick won 143 total points in this match, Murray 141; how’s that for a fair fight?), these two dandy Andys didn’t create much daylight between them. The difference between a fifth set and crushing heartbreak for all England would once again come down to two points out of the 284 that were played on Friday. As was the case in set three, Roddick would own that precious pair.

The first key point of the tiebreak emerged at 2-1 Roddick, when Murray-on serve-lost hold of a forehand that sailed long and gave the American a mini-break lead, which meant a lot given the way the rest of the fourth set proceeded. Roddick successfully hit 75 percent of his first serves, and in the crucible of a fourth-set breaker, the sixth seed soared on serve. Slamming an ace or a service winner on each of his first five service points, Roddick gained double match point at 6-4. It was only then that Roddick failed to put a first serve in the court, and Murray-much to his credit-took advantage of the second ball by ripping a terrific passing shot to get back on serve at 5-6. Roddick still had a match point, but his dogged opponent now had the next two serves on his racket. It would take something special for the American to win on the court that Tim Henman couldn’t quite master, and which Murray hoped to own come Sunday evening against Federer.

Speaking of Federer, that’s the player Roddick evoked with the way he played his second match point. On the 12th point of this terrific tiebreak-the point that would make all the difference in a match that was worthy of a Wimbledon semifinal-Roddick did what Federer had done to him so many times before.

In their 2003 Wimbledon semifinal, and then back-to-back meetings in the 2004 and 2005 finals of The Championships, Federer foiled Roddick with one play above all others: the blocked first-serve return. This is not a return that’s meant to produce a winner, nor is it a service return meant to generate any kind of power or spin. The blocked return is simply an attempt to retrieve a bullet-like serve far enough into the court to prevent the server from having an easy put-away on the follow-up shot. If a blocked service return lands anywhere near the baseline, the server-contemplating his next move-must decide whether to hit an overhead or a forehand. The overhead could finish the point, but it carries more risk. The forehand is a higher-percentage shot, but it is less likely to produce an outright winner. The blocked return, then, allows a service receiver to establish a somewhat neutral position despite a 130-mile-per-hour bomb delivered by the server. It’s not a sexy play, and it doesn’t show up in highlights or stat sheets, but the blocked return is a winning play on grass, and it enabled Federer to win those three straight Wimbledon matches over Roddick, on the way to singles titles in each of those three years (2003-’05).

Simply stated, this 5-6 point began with a huge Murray first serve to the ad court corner of the service box. Roddick is not known for his return game (much as he entered this match with a reputation as a mediocre net player), but on this one occasion, he managed to block back a return within three feet of the baseline. Murray-who would normally have won a point with the huge first serve he just thundered-instead had to play a medium-pace forehand that allowed Roddick to get into that all-important netural position. Just a few strokes later, Roddick worked his way to the net behind something solid, and when Murray couldn’t hit the passing shot, the upset had been completed in the most ironic of ways: Andy Roddick, so often the victim of a blocked return at the hands of Roger Federer, had advanced to another Wimbledon final against his Swiss nemesis by imitating Federer in the heat of competition.

Murray-who cracked 76 winners and committed just 20 unforced errors-will only lament his 52 percent first-serve conversion rate, the one stat that truly hampered the British hope more than anything else. Other than his balky serve, the world No. 3 could not argue with the way he played. Murray simply ran into a man who-four years removed from his last Wimbledon final, and three years removed from his last Grand Slam finals appearance (the 2006 U.S. Open, also against Federer)-summoned forth the grittiest and gutsiest big-point tennis of his life.

Andy Roddick couldn’t have known that he would get back to the big stage on the final Sunday of any slam, let alone Wimbledon. Doubt and uncertainty have marked the past few years of an athletic odyssey pockmarked with potholes and stumbles and searing disappointments. But now, after conjuring up a considerable amount of courage in the face of a crowd that wanted the other Andy to win, Mr. Roddick has to feel that he can overcome any future challenges that come his way.

Sunday, that challenge is named Roger Federer. Cause for concern? Sure. Cause for fear or worry? Not for a man who has seen all the highs and lows of life on the ATP Tour, especially since the last time he faced Fed in a Wimbledon final.

Andy Roddick-fresh off the heels of this life-changing Friday in suburban London-will give everything he has when he faces Federer, and “everything” amounts to a lot when Roddick is the topic of discussion. Andy Murray could tell you as much after a superb semifinal showdown that created a wonderful and inspiring story… just not the one the British people were hoping to read in the Saturday papers.

Tags:

No Comments »

No comments yet.

RSS feed for comments on this post.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.